Psychotherapy Treatment Plans & Progress Notes Can Have Chilling Effects on Patients, Outcomes, Satisfaction & Dropout

The clinical, legal, ethical, and contractual requirements for charting have become so extensive, bureaucratic, and without clinical purpose, that charting requirements are impossible to fulfill for every patient.

Requirements for psychotherapy chart notes do not improve outcomes, and when followed, can cause premature dropout.

Healthplans take shelter in their assertion that private, personal, and sensitive information is necessary, ignoring the ethical concern that “too much” information may later come back to harm a patient.

Many Healthplan’s charting requirements expect psychotherapists to risk betraying patients’ confidence by documenting private, personal, and sensitive information in a patient’s medical record to justify services.

AMHA-OR and Mentor Research Institute (MRI) are affirming, with evidence, a widely held belief among psychotherapists that psychotherapy charting, as required in Healthplans contracts, is (1) not aligned with patient privacy rights, (2) wasting tax payer, employer and patients’ money, and (3) has chilling effects on patients, services, and psychotherapy outcomes.

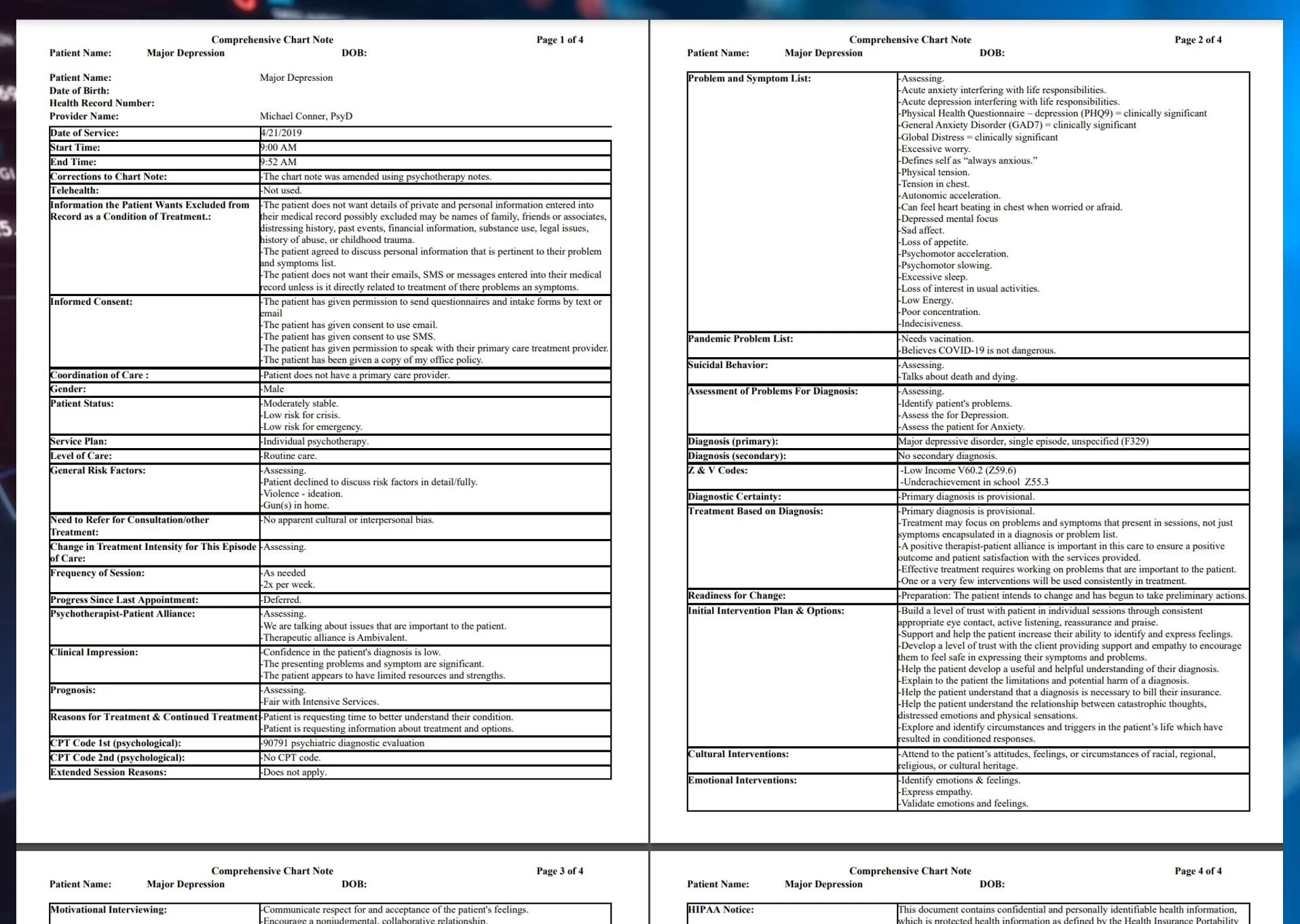

98% compliance can require as many as 10 pages per comprehensive chart note.

In 2021, MRI conducted an extensive review of psychotherapy charting requirements and training for psychotherapists who contract with the Oregon Health Authority, Medicare, Medicaid and several commercial Healthplan payers. This was in response to concerns expressed by AMHA-OR members about charting requirements and potential audits by Healthplan payers.

For more information see:

What is the Value of Charting in Psychotherapy Practice?

https://www.mentorresearch.org/value-psychotherapy-charting

During their review process AMHA-OR, MRI and Private Practice Cloud (PPC) developed a software charting simulator that can be used for training based on Healthplans’ charting requirements. The software was named Grid Charting because it allows users to view chart notes in a manner similar to a spreadsheet grid. In the grid each column in the spreadsheet is a chart note. Each row includes a category of information associated with a specific charting requirement. For example, Symptoms and Problems is a category used to document the basis for a diagnosis. Using the Grid allows psychotherapists to view informed consent, demographics, coding, treatment plans, progress notes, practice guidelines and audit requirements in one column. The entire record can be viewed the same way a spreadsheet is viewed.

Following is an overview of Grid Charting Training features and overall functions:

The dashboard and user preferences (i.e. settings) allow a user to configure, display and analyze the quality and compliance of a chart note and of the entire patient record.

The user can select the compliance quality and level of detail they wish to use for a chart note.

The user can select categories they believe are necessary to meet specific compliance requirements.

Presenting symptom and problem burden can be used as patient reported outcome measures focusing on symptoms and problems rather than the symptomatic consequences.

Suggestions, templates and options within each category can be selected and edited.

The user can “audit” specific notes or an entire record by clicking a button.

The user can also visually audit the record using a self-audit checklist feature which can be attached to each chart note.

Clinical practice guidelines can be attached to and edited for each chart note or for an entire record.

Put simply, using the grid reveals the compliance demands for chart note documentation, 3rd party requirements, and review and audit procedures. The Grid is designed to be a comprehensive training and feedback system to train and support psychotherapists’ needing to deal with charting requirements.

Charting Requirements are Extensive, Meaningless and May Harm Patients

As an unexpected outcome, the software provides important insight into the time and training required to satisfy State and Federal Laws and payer contract demands. More important, Grid Charting reveals why and how far therapists must go to be compliant with contacts. The Grid template creates dynamic documents and illustrates many reasons why some electronic charting systems are being abandoned and why a majority of psychotherapists keep paper notes to protect their patients and themselves.

The clinical, legal, ethical, and contractual requirements for charting have become so extensive, bureaucratic, and without clinical purpose, that charting requirements are impossible to fulfill for every patient.

Healthplan contracts, State and Federal Law are not aligned. The explicit and implicit expectations of each set of requirements can be arbitrary, can conflict with each other, are vague in many ways, waste time; they undermine mental health services, patient satisfaction and outcomes. The required duplications of effort create a burden that is punishing. Healthplans create these requirements arbitrarily and make no effort to communicate with psychotherapists about their supposed reliability, validity, usefulness, or impact on patients and psychotherapists.

Lack of Empirical or Evidence-Based Research to Support Charting Requirements

The dominant psychotherapy charting requirements are outdated and ignore 40-plus years of research which demonstrate that evidence-based charting systems could actually improve outcomes and protect patients. Providers in training no longer review chart notes to learn how to be better psychotherapists. Their supervisors read chart notes to ensure psychotherapists adhere to bureaucratic requirements.

Ironically, behavioral health providers and Healthplans are powerless to change the status quo, in large part because requirements created decades ago (as proposed solutions to increasing costs) have become industry standards unsupported by patient satisfaction or outcome studies.

Requirements for psychotherapy chart notes do not improve outcomes, and when followed, can cause premature dropout. Healthplan’s charting requirements expect psychotherapists to risk betraying patients’ confidence by documenting private, personal, sensitive information in a patient’s medical record to justify services. Healthplans taking shelter in the chasm between fact and their assertion that such information is necessary, ignore the ethical concern that “too much” information may later come back to harm a patient.

New Laws and Demands

New Federal and State laws require providers to make their treatment records available to patients quickly and in some cases immediately; even when documents are in draft format. As a result, psychotherapists must carefully consider what they place in patients’ medical records. This takes time, requires training and clear office policies. Without industry standards, and out of concern for patients, psychotherapists often resort to minimum necessary charting.

The Impact of Charting on Psychotherapy Operations

Anyone using the the grid will see immediately how far they are “out of compliance”, and/or to what extent they are “in compliance” with State and Federal Regulations and Healthplan contracts. They will see evidence of how difficult charting has become. Students, interns and residents being trained in inpatient, day treatment and or other supervised settings will see how unprepared they are to meet the bureaucratic charting demands of clinical practice.

Further, providers will become more aware, when using other charting strategies, to what extent they may be at the mercy of auditors who could justify “clawbacks” of money based on assertions of contract violation and/or failure to demonstrate medical necessity. The operational demands of a psychotherapy practice, the functionality of electronic health records, and the broad range of contract requirements almost guarantee that psychotherapists will fail audits. An auditor’s process and decision as to whether a psychotherapist is (1) warned, or (2) required to pay money back to a Healthplan, can take months. Most Healthplans require repayment before allowing a psychotherapist to appeal the company’s demand for payment return. Programs in the U.S. have been bankrupted waiting for the results of aggressive audits.

The Impact on Psychotherapists

According to the Centers for Disease Control …surveys found about 38% of respondents reported symptoms of anxiety or depression from April 2020 through Feb. 2021—up from about 11% in 2019. According to the U.S Government Accountability Office, Doctors, nurses, and other frontline workers are also at an increased risk for developing mental health conditions, including post-traumatic stress syndrome. The frustration psychotherapists have about charting requirements has an emotional impact. Frustration can lead to apathy, and apathy leads to psychotherapists’ depression and burnout. That in turn challenges therapists to work less and/or limit the type of patients they will treat. Providing services during the pandemic has taken a toll on those in front line positions. This may explain why a majority of psychotherapists do not use electronic health records, prefer to keep paper notes, and are unaware of the degree to which they may be out of compliance with Federal regulations, State regulations, and their Healthplan contracts.

Private Practice Cloud, LLC provides technology and consultation to AMHA-OR.

References

APA. (2020). Guidelines for the Practice of Telepsychology. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/practice/guidelines/telepsychology

HHS.gov. (2020). The HIPAA Privacy Rule. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/index.html

Yale.edu. (2020). Clinician's Guide to HIPAA Privacy. https://hipaa.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/HIPAA-Clinician-inside.pdf

Record Keeping Guidelines

https://www.apa.org/practice/guidelines/record-keepingAmerican Psychological Association. (2007). Record keeping guidelines. American Psychologist, 62(9), 993.

What is the Value of Charting in Psychotherapy Practice?

https://www.mentorresearch.org/value-psychotherapy-chartingTreatment Manuals Do not Improve Outcomes

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237297802Evidence-Based Practice in Psychology

https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/features/evidence-based-statement.pdfPolicy Statement on Evidence-Based Practice in Psychology

https://www.apa.org/practice/guidelines/evidence-based-statementClinical Record Keeping in Psychological Practice - Complete, Accurate Ethical?

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312328870Behavioral Health: Patient Access, Provider Claims Payment, and the Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-437r

APA Reference List

American Psychological Association. (2002a). Criteria for practice guideline development and evaluation. American Psychologist, 57, 1048- 1051.

American Psychological Association. (2002b). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist, 57, 1060- 1073.

American Psychological Association. (2005). Determination and documentation of the need for practice guidelines. American Psychologist, 60, 976-978.

American Psychological Association, Committee on Legal Issues. (2006). Strategies for private practitioners coping with subpoenas or compelled testimony for client records or test data. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37, 215-222.

American Psychological Association, Committee on Professional Practice and Standards. (1993). Record keeping guidelines. American Psychologist, 48, 984-986.

American Psychological Association, Committee on Professional Practice and Standards. (2003). Legal issues in the professional practice of psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34, 595- 600.

Benefield, H., Ashkanazi, G., & Rozensky, R. H. (2006). Communication and records: HIPAA issues when working in health care settings. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37, 273-277.

Falvey, J. E., & Cohen, C. R. (2003). The buck stops here: Documenting clinical supervision. Clinical Supervisor, 22, 63-80.

Fisher, C. (2003). Decoding the ethics code: A practical guide for psychologists. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kennedy, P. F., Vandehey, M., Norman, W. B., & Diekhoff, G. M. (2003). Recommendations for risk-management practices. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34, 309-311.

Knapp, S., & VandeCreek, L. (2003a). A guide to the 2002 revision of the American Psychological Association's ethics code. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resources Press.

Knapp, S., & VandeCreek, L. (2003b). An overview of the major changes in the 2002 APA Ethics Code. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34, 301-308.

Koocher, G. P., & Keith-Spiegel, P. (1998). Ethics in psychology: Professional standards and cases. New York: Oxford University Press.

Koocher, G. P., Norcross, J.C., & Hill, S. S., III. (Eds.). (1998). Psychologist's desk reference. New York: Oxford University Press.

Luepker, E. T. (2003). Record keeping in psychotherapy and counseling: Protecting confidentiality and the professional relationship. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Merlone, L. (2005). Record keeping and the school counselor. Professional School Counseling, 8, 372-376.

Moline, M. E., Williams, G. T., & Austin, K. M. (1998). Documenting psychotherapy: Essentials for mental health practitioners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Zuckerman, E. (2003). The paper office (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Content

Barnett, J. (1999). Documentation: Can you have too much of a good thing? (Or too little?) Psychotherapy Bulletin, 34, 19-21.

Fulero, S. M., & Wilbert, J. R. (1988). Record-keeping practices of clinical and counseling psychologists: A survey of practitioners. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice, 19, 658-660.

Soisson, E. L., VandeCreek, L., & Knapp, S. (1987). Thorough record keeping: A good defense in a litigious era. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 18, 498-502.

Disposition of Records

Halloway, J. D. (2003). Professional will: A responsible thing to do. APA Monitor, 34, 34-35.

Koocher, G. P. (2003). Ethical and legal issues in professional practice transitions. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34, 383-387.

McGee, T. F. (2003). Observations on the retirement of professional psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34, 388-395.

Informed Consent

Pomeranz, A. M., & Handelsman, M. M. (2004). Informed consent revisited: An updated written question format. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35, 201-205.

Multiple Client Records

Gustafson, K. E., & McNamara, J. R. (1987). Confidentiality with minors. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice, 18, 503-508.

Marsh, D. T., & Magee, R. D. (Eds.). (1997). Ethical and legal issues in professional practice with families. New York: Wiley.

Patten, C., Barnett, T., & Houlihan, D. (1991). Ethics in marital and family therapy: A review of the literature. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 22, 171-175.

Patterson, T. E. (1999). Couple and family documentation sourcebook. New York: Wiley.

Technology

Barnett, J. E., & Scheetz, K. (2003). Technological advances and telehealth: Ethics, law, and the practice of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 40, 86-93.

Cartwright, M., Gibbon, P., McDermott, B. M., & Bor, W. (2005). The use of email in a child and adolescent mental health service: Are staff ready? Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 11, 199-204.

Jacovino, L. (2004). The patient-therapist relationship: Reliable and authentic mental health records in a shared electronic environment. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law, 11, 63-72.

Jerome, L. W., DeLeon, P. H., James, L. C., Folen, R., Earles, J., & Gedney, J. J. (2000). The coming of age of telecommunications in psychological research and practice. American Psychologist, 55, 407-421.

McMinn, M. R., Buchanan, T., Ellens, B. M., & Ryan, M. K. (1999). Technology, professional practice, and ethics: Survey findings and implications. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 30, 165-172.

Murphy, M. J. (2003). Computer technology for office-based psychological practice: Applications and factors affecting adoption. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 40, 10-19.

Reed, G. M., McLaughlin, C. J., & Milholland, K. (2000). Ten interdisciplinary principles for professional practice in telehealth: Implications for psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31, 170-178.

Salib, J. C., & Murphy, M. J. (2003). Factors associated with technology adoption in private practice settings. Independent Practitioner, 23, 72-76.

Privacy and Confidentiality

Knapp, S. J., & VandeCreek, L. D. (2006). Confidentiality, privileged communications, and record keeping. In Practical ethics for psychologists: A positive approach (pp. 111-128). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.